Articles

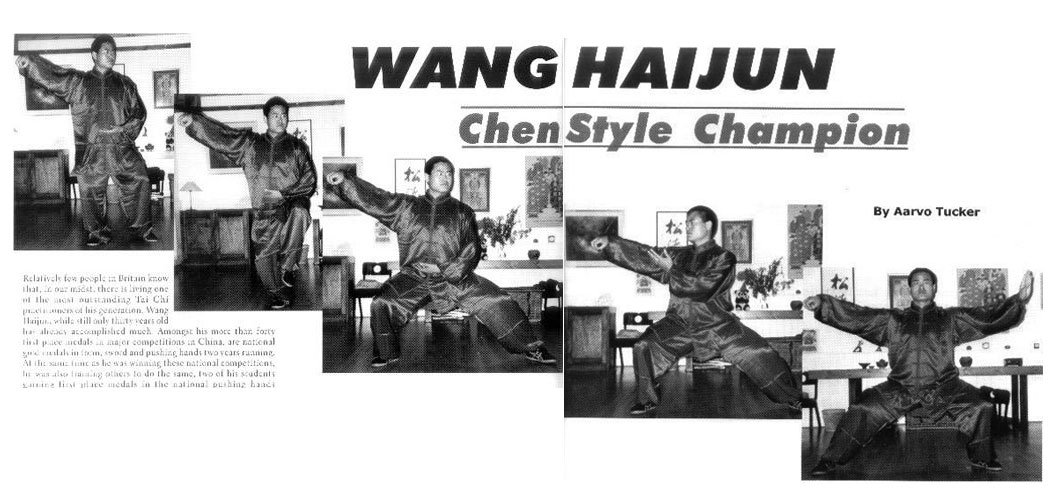

Relatively few people in Britain know that, in our midst, there is living one of the most outstanding Tai Chi practitioners of its generation. Wang Haijun, while still only thirty years old has already accomplished much. Amongst his more than forty first place medals in major competitions in China, are national gold medals in form, sword and pushing hands two years running. At the same time as he was winning these national competitions, he was also training others to do the same, two of his students gaining first place medals in the national pushing hands championships.

And so how did he accomplish so much so fast? Well, first of all, he started at a young age with one of the most highly regarded teachers in China, Chen Zhenglei. Wang’s father was very keen on martial arts, and seeing the same interest in his young son, he arranged, through a friend, who was close friends with Chen Zhenglei, for his son to live at Chen’s house in Chen village. From the age of nine Wang Haijun had high quality daily instruction which, in addition to natural talent, and appetite for hard work, and the time he set aside for his daily training, has resulted in his incredible achievements so far.

Wang estimates that 80-90% of the Chen Villagers practice Taijiquan. Since the area around Chen Village is mainly agricultural, often, after working in the fields, people would practice the form a few times, to stretch their legs and give their bodies and minds a sense of well-being. With his main activity being to learn Tai Chi, Wang was on a much moer intensive training schedule—three times a day, the first session starting at 5:30am until breakfast at 7 o’clock. Then he was off to school, coming home for lunch before going back to school in the afternoon. After school, he practiced from 4 until 6pm, and then had dinner. He would let his food settle for 30-40 minutes and then practice in the evening for another couple of hours.

In those days, before Taijiquan had the degree of government sponsorship that it now has, his teacher, Chen Zhenglei, worker as a salesman of electrical machinery, which required that he sometimes be away on business. However, when he was at home, he generally gave instruction in the afternoon training session, sharing the finer points of the form. For the first six years of his training Wang Haijun focused solely on the Chen first form, not doing any pushing hands, applications or weapons until much later. These six years were spent form training to help to build a strong foundation. He feels that the kind of strength and movement that are developed in Tai Chi are hard to describe in words and must be experienced through long practice which facilitates a deep body understanding. When this foundation work is done the ‘root becomes strong, the internal Qi becomes full’ and then the other forms are easy and simple.

Nowadays with the opening of China and the greater exposure of Chen style Tai Chi, many people from around the country, and indeed from around the world, go to the origin of Tai Chi to seek out instruction. However twenty years ago this was not the case. In the early to mid eighties, there were often just few outsiders, and the practice sessions were often just a handful of people training. In such an environment, with that amount of individual attention and more intense time spent with the teacher, growing up almost as part of Chen Zhenglei’s family, the hopes and expectation for Wang’s Tai Chi development were high. At the age of sixteen he went off to the Wuhan Sports Institute as a specially admitted student, and after graduation he got assigned a work unit, which was the Pingdingshan Martial Arts Academy where he was reunited with Chen Zhenglei who was now the head of the academy.

It was around this time that he began his career in Taijiquan competitions. In 1992 he entered the national pushing hands competition and got a first place medal. During 1993 he traveled with his teacher to several countries giving demonstrations and assisting in workshops. In 1994 he won the national pushing hands championship in the 80 kilogram weight division. In 1996 he also won gold medals in national championships, and then the pinnacle of his career in competitions was two consecutive years (1997-1998) winning the three categories of Taiji form, sword and pushing hands in the biggest national tournament which brought him the title of overall champion.

In the martial arts world there are many tournaments, the significance and standards of which vary widely. The names may be misleading. The titles national and international maybe bandied about without it meaning very much. In some tournaments there may only be a few contestants in a particular category or weight division—with only three contestants, each will get a medal regardless of performance. In these tournaments, Wang was against the best of the best—people who were selected from each province to vie for most important national titles.

At the same time of this personal success in 1997, he established a martial arts school in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province. The team he trained and led into competition was the highest scoring of all teams in a 1998 national tournament, and he trained many students to good results; two of whom won national pushing hands competitions at 52 kgs in 1997 and 65 kgs in 1998. These students express great devotion to him, and speak of Wang as a highly accomplished master of the art, who remains a quiet-spoken, dignified and direct man—someone who is exemplary in the personal qualities of the traditional Chinese martial artist. One of his students quoted the Chinese phrase: ‘Being able to eat the bitterest of the bitter, one can be a man above men’. Rectitude, humility, courtesy are what stuck me when I first met him, as apparent as his serous attitude toward Taijiquan. Not one for self-promotion or talking about himself, I was glad that his wife was willing to tell me things about him.

His wife is an accomplished wushu person in her won right, having gained national gold medals in straight sword, broadsword, and two person routines. She worked for many years as a wushu coach, and is called Jia Laoshi by Wang’s students. Their daughter, a lively, bright-eyes girl of five has the advantages of strong genetic inheritance and excellent instruction available, but her mother, having gone through the hardship of training from a very young age, getting up early in all kinds of weather to train while friends and classmates could sleep in, wants her daughter to have an easier childhood. Wang, on the other hand, hopes she will earn something of the art which he has spent most his life practicing.

Wang Haijun talks about some attributes that people doing Taiji and all athletes must develop: stamina and strength are developed through form practice, explosive power through more specialized training, such as pole shaking exercises and single movement drills, and flexibility which he considers to be not as important as in some other sports, but which is developed gradually through form practice. As to the question of weight training to supplement Taijiquan training, Wang states that if you can do it in a relaxed way, some of that type of training should be all right.

In 1997 the Chinese martial arts council held an important conference to study and discuss pushing hands competition rules. Top Taiji teachers and competitors from around the country were invited to attend and contribute. Wang was one of the participants in the conference and mentioned that one of the main topics of discussion was about which techniques would be allowed. Some of the decisions they arrived at were that the traditional eight techniques of Taiji—peng, lu, ji, an, cai, lie, zhou, kao would be allowed, but for safety’s sake only the sides and not the points of the elbows may be used; the use of the legs must be limited to techniques such as tripping in which the feet stay on the ground (no large sweeping/kicking movements of the legs).

In Wang’s training in Chen village, and in some of the regional competitions, they did moving step pushing hands: moving forwards and back in a pattern. He believes that training in this way makes it more likely to adhere to the Taiji principles of avoiding the opponents force and not resisting directly. The downside however is that there tends to be more injuries. The national competitions have now adopted the fixed feet rules, which he feels are less ideal for displaying Taiji principles of engagement but result in fewer injuries.

With the large Chen style curriculum to practice, Wang says his own practice still focuses on the Laojia Yilu—the old first form—and then the second form (Pao Chui) and the ‘new form’ versions of these two. With respect to the various weapon forms; by practicing them once a week he gets the footwork and body movement training from them, but feels if the basic form is good then the weapons will be correspondingly good. He quoted a famous dictum: ‘Practice the form and not just techniques’.

In his teaching, he puts quite a bit of emphasis on the Silk Reeling Exercises as a ways of instilling the basic movement principles of Taijiquan. They are relatively new development in the history of Chen style, but are used by many well-known teachers. Next he generally teaches the Laojia Yilu (the old style first form), which he says was traditionally used as a first test of prospective students to see how seriously they practiced and to see about their character. It is also the main gongfu building form—the foundation for the rest of the system. Wang recognizes that people of today live in a wholly more complex society, with a greater number of distractions, entertainments, choices, and much more information available, and much less time with their instructor than in earlier times. Consequently he teaches students more quickly, feeding them new movements at a faster rate. When he was learning he accepted whatever his teacher taught, and at whatever pace, however slowly. People nowadays would not generally have the patience for that, but when you see the result in Wang Haijun’s level of skill, it is difficult not to appreciate the ‘slow cook’ method.